Keeping browser tabs in sync using localStorage, NgRx, and RxJS

Update: Depending on the use case, the Broadcast Channel API might be better compared to using the Local Storage. The idea behind this post will still remain the same, and the code will almost look identical. Just, swap out local storage with a broadcast channel.

In this post, we’re going to take a look at how we can keep our application state in sync when a user has multiple tabs open. We’re going to make this happen by using the Web Storage API, NgRx (Store and Effects), and RxJS. Basic knowledge of NgRx is needed to follow the examples.

There are two ways of syncing state that I know of. One of them is to send the actions from one tab to another tab, the other is to send the (partial) state from one tab to another tab. While both of these ways have very similar implementations, they both shine in their own way.

As a starting point, we’re going to pick up where we left off in a previous post Let’s have a chat about Actions and Action Creators within NgRx where we created a simple grocery list.

Syncing state by sending actions from one tab to another tab link

Knowing that our state is predictable because we’re using NgRx to manage the state of our application, we can leverage its power to rebuild the state. Thus if we store every dispatched action into the local storage and we dispatch them again in the same order, we know that we will have the same outcome, i.e. the same state. If you’re familiar with the Redux DevTools Extension, you have probably already used or at least seen this concept by rewinding and replaying actions.

The first step to the solution is to store actions to the local storage.

format_quoteWe’re using local storage because this means that every tab with the same origin can access it; as opposed to session storage, which creates a new storage for every tab.

Storing actions to local storage link

To store the actions we’ll be using an effect, listening to a certain set of actions because (in most of the cases) we only want to store actions not triggering a side effect. We can take a look at a simple example of fetching a list of items from a back-end. In this case, we don’t want to store the LOAD_ITEMS action because this would mean that we’ll also fetch the items again from a back-end. This action of fetching items isn’t pure, because in the worst case we could end up with a different set of items every time we make a new HTTP request. What we (usually) want is to store the LOAD_ITEMS_SUCCESS action, because this action contains meaningful data as its payload, to share across tabs and is pure.

In our grocery list, these meaningful actions are when a grocery has been added, checked off, or removed from the list. The implementation to intercept actions and store them to local storage looks like the following snippet:

If you’re not familiar with the storage API, you can compare it to a key (string) value (string) collection. It has a getItem method to retrieve the stored item (actions in our case) and a setItem to insert or update a value (actions in our case), based on the key. To know more about the API you can take a look at the MDN web docs.

Note that we can’t just simply store and retrieve the actions from the local storage. We have to serialize each action with JSON.stringify, and then deserialize the value with JSON.parse to recreate the action. In an application using NgRx, we can assume that actions are serializable.

Retrieving actions from local storage and dispatching them link

Now that we’ve stored the actions inside our local storage, the next step is to notify the other tabs and dispatch the same actions there. Here again, we’re also going to use an effect. We use the RxJS function fromEvent to listen to the browser event window.storage and get notified when the local storage changes in another tab.

format_quoteThe

StorageEventis fired whenever a change is made to theStorageobject (note that this event is not fired for sessionStorage changes). This won't work on the same page that is making the changes — it is really a way for other pages on the domain using the storage to sync any changes that are made. Pages on other domains can't access the same storage objects. — MDN web docs

These two snippets should be enough to show a small demo on how the grocery list behaves:

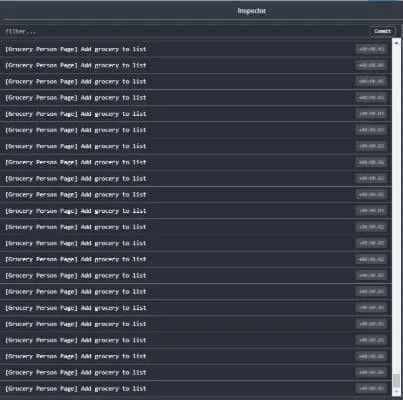

As you can see in the GIF above, when we add a grocery in the top page, the two pages at the bottom also get updated. But if you take a closer look, you can also see that after the first action is dispatched (when we add apples to the list) the application gets a bit stuck. After the second action (when we added pears) the application more or less froze. What could be the cause here? Well, if we take a look at the Redux DevTools we can have a better understanding of what causes this behavior.

We’re stuck in an infinite loop. Because we’re storing an action and re-dispatching it in another tab and then also storing the dispatched action, another tab will pick this change up which restarts the whole flow all over again. The first solution that comes to mind is to add an extra property to the action to let the effect know whether it needs to store the action or not. The re-dispatched action could, for example, have the property storeToStorage: false. This solution violates Good Action Hygiene. To solve it in a more readable way and follow the good action hygiene practice, we’ll create new actions for every stored action. These new actions won’t get stored to the local storage because they aren’t added inside the filter, thus not restarting the whole flow. To re-dispatch the stored action we have to convert it to a new event. We do this inside the effect, using a switch case:

Et voila, we’ve got a working demo. As you can see in the GIF above the “Toggle checked off groceries” isn’t synced to the other tabs, this is because we don’t store this action in the local storage.

Syncing state by sending the state from one tab to another link

This way of syncing state across tabs uses the same techniques as the first one. But the difference is that we store the whole state in the local storage.

Storing state to local storage link

In the grocery list application, we already have a meta-reducer that does exactly this. The persistStateReducer reducer persists the state to the local storage to reload the state when we reopen the grocery list. Therefore, we don’t have to change anything for this step.

format_quoteIt’s also possible to persist state to local storage by using an effect, take a look at the angular-ngrx-material-starter project by Tomas Trajan for an example.

Updating the state tree link

To read the state in another tab we’re going to use the same method as we did before. The big difference here is that we don’t dispatch actions to rebuild the state. We’re going to dispatch an action containing the whole state or a partial state as its payload.

Now the only thing left to do is to update the state. We can do this by adding a case statement in the reducer or creating a second meta-reducer. Personally, I prefer to create a meta-reducer because it lives a bit “outside” of the application itself and doesn’t really contain any logic. We simply replace the current state with the new state. Another point is that we already have the persistStateReducer meta-reducer to store state to local storage.

This gives us the same result as before, but in a slightly different way:

Conclusion link

In a redux-based system, like NgRx, I find it simple and straightforward to handle different event sources, just to name a few: user interaction, browser events, communication with a web API, and so forth.

By using @ngrx/effects in combination with RxJS it’s possible to write the stream of these events in just a few lines of codes, while not decreasing the readability of our code.

Both approaches do have their pros and cons. With the action-based approach, you have more control over the flow. But, the downside is that you have to maintain more code. The action-based approach also allows you to invoke side effects. The state-based approach is the opposite. With just a couple of lines, you can start syncing state but you pay a price in controllability.

The examples from this post can be found on GitHub.

Outgoing links

Feel free to update this blog post on GitHub, thanks in advance!

Join My Newsletter (WIP)

Join my weekly newsletter to receive my latest blog posts and bits, directly in your inbox.

Support me

I appreciate it if you would support me if have you enjoyed this post and found it useful, thank you in advance.